By Ripley Cook

Etymology: The Demigod Kui’s Bird

First Described By: Worthy et al., 2010

Classification: Dinosauromorpha, Dinosauriformes, Dracohors, Dinosauria, Saurischia, Eusaurischia, Theropoda, Neotheropoda, Averostra, Tetanurae, Orionides, Avetheropoda, Coelurosauria, Tyrannoraptora, Maniraptoriformes, Maniraptora, Pennaraptora, Paraves, Eumaniraptora, Averaptora, Avialae, Euavialae, Avebrevicauda, Pygostylia, Ornithothoraces, Euornithes, Ornithuromorpha, Ornithurae, Neornithes, Neognathae, Neoaves, Australaves, Psittacopasserae, Passeriformes, Acanthisitti, Acanthisittidae

Status: Extinct

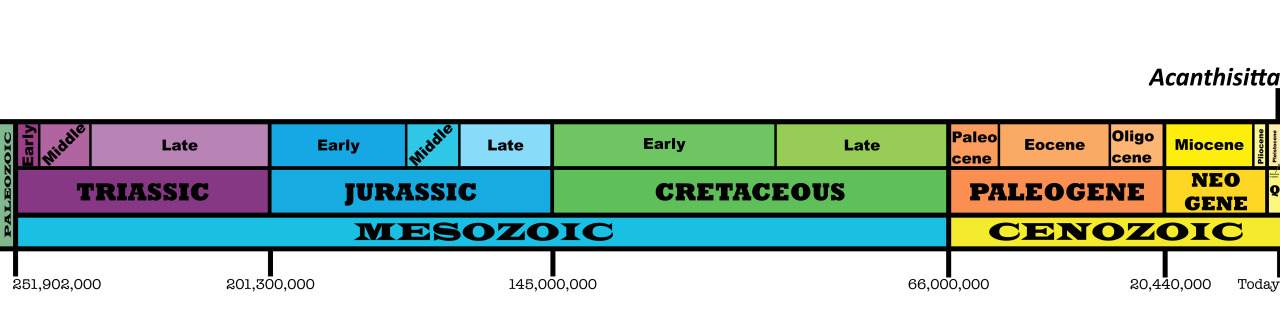

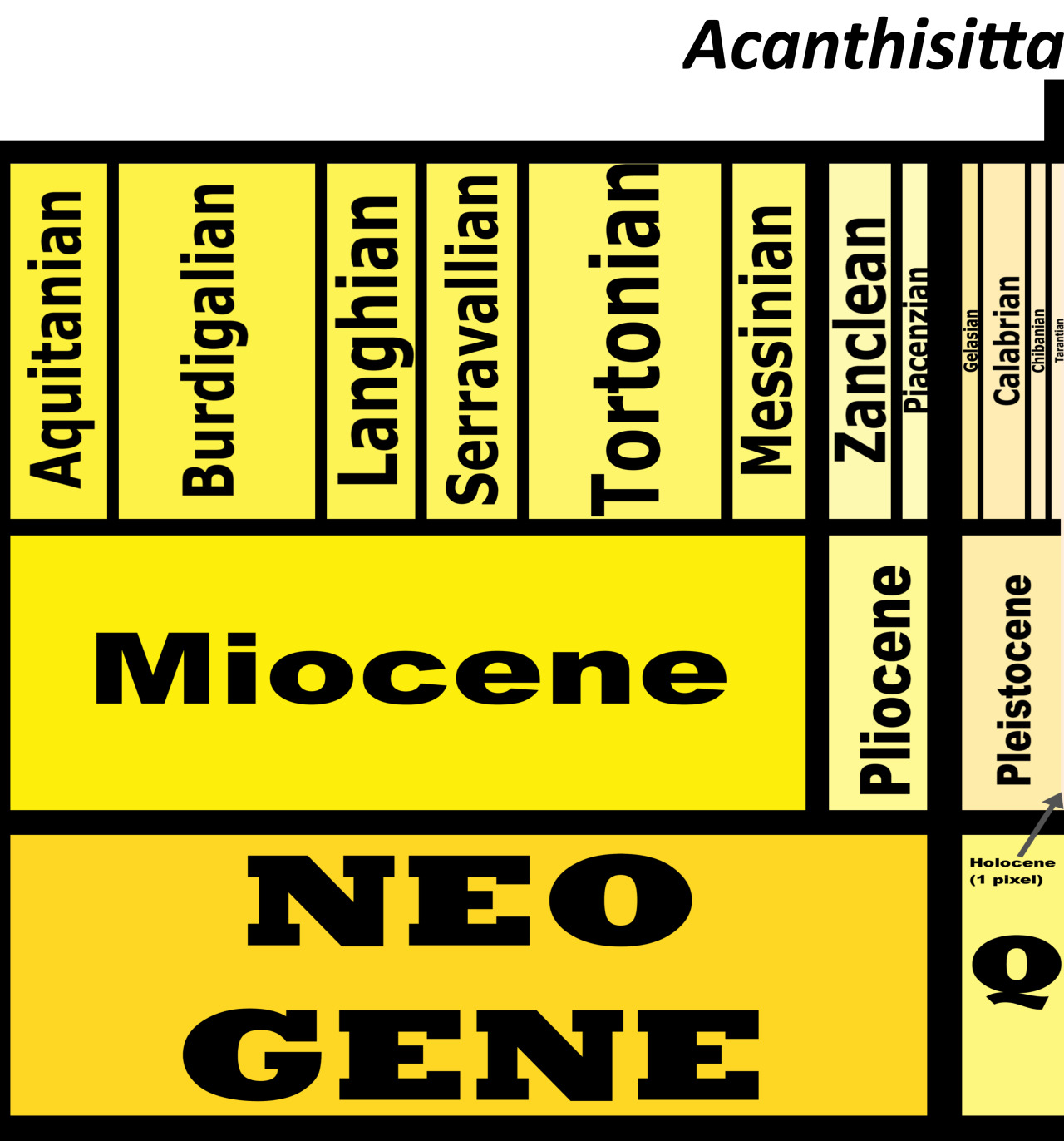

Time and Place: Between 19 and 16 million years ago, in the Burdigalian of the Miocene

Kuiornis is from the Saint Bathans Fauna, a distinctive snapshot of the evolution of New Zealand’s unique birds – from the Bannockburn Formation of the South Island of New Zealand

Physical Description: Kuiornis is known from limb elements, so we don’t know much about it, but it seems to have been only a little smaller than the living Rifleman, its closest relative – so it was probably around 7 centimeters long. It would have looked similar to the living Rifleman as well – a round bird, with a distinctively thin tail, and a small head with a triangular beak. As for differences from living New Zealand Wrens, it had differently formed and more compact legs. Beyond this, it’s difficult to say more about the specific appearance of Kuiornis; it probably would have been green and brown in color, like its living relatives.

Diet: Without fossil evidence of the beak, we have to assume that Kuiornis was an omnivore; given that New Zealand Wrens today favor invertebrates but still eat other forms of food, this is not an unreasonable assumption.

Behavior: Kuiornis would have been very skittish like modern New Zealand Wrens, flitting back and forth between the shrubs and vegetation in its habitat. It would have probably been only moderately social, like living New Zealand Wrens, and making high pitched, non-musical calls. Kuiornis would then spend most of its time foraging for food. When not doing that, it would have taken care of its young, building nests out of grass and in secluded spaces. It is difficult to say much about its breeding behavior – or behavior in general – however, since very little is known from this dinosaur.

Ecosystem: At the end of the Paleogene, New Zealand flooded. This completely erased the previous ecosystem, killing most things that had been on the island before that point. Afterwards, the only things that were able to colonize the space were creatures that floated over, and creatures that could fly. This included lizards and snakes and other reptiles, bats, and most notably of all – birds. New Zealand had one of the most unique avifaunas of all time, with many birds evolving to fill roles that mammals took in other locations – things like the moas, the large birds of prey, the adzebills, and living forms like the New Zealand Parrots that are like avian rodents and rabbits. The Saint Bathans Fauna is a snapshot of that initial colonization, showing how these unique birds began to diversify after New Zealand reemerged, in a lush lake enviroment. Kuiornis is just one part of that – showing the origin of the weird New Zealand Wrens. There was also the early Kiwi Proapteryx, the small Manuherikia ducks, the stiff-tailed Dunstanneta, the shelduck Miotadorna, the goose Cereopsis, the wood duck Matanas, the weird pigeon Rupephaps, the early Adzebill Aptornis proasciarostratus, the flightless rails Priscaweka and Litorallus, the swimming flamingo Palaelodus, the herons Matuku and Pikaihao, the bittern Pikaihao, the New Zealand Parrot Nelepsittacus, and potential eagles and hawks. There were also many geckos, skinks, crocodilians, turtles, and tuatara present as well. Weirdly enough, there was a mammal other than bats – but that mammal is what we would call a Mystery.

Other: Kuiornis has been extensively studied in phylogenetic analyses, and these analyses consistently recover Kuiornis as a New Zealand Wren, so it is an important find in understanding how this unique group of little dinosaurs evolved in such an isolated environment as New Zealand. Interestingly enough, it consistently comes out as very much nested in the group, extremely closely related to the Rifleman. This indicates that Kuiornis is not a decent model for the ancestor of the New Zealand Wrens, and also that advanced members of this group were present as recent as the mid-Neogene period.

~ By Meig Dickson

Sources under the Cut