By Scott Reid

Etymology: Chicken Mimic

First Described By: Osmólska et al., 1972

Classification: Dinosauromorpha, Dinosauriformes, Dracohors, Dinosauria, Saurischia, Eusaurischia, Theropoda, Neotheropoda, Averostra, Tetanurae, Orionides, Avetheropoda, Coelurosauria, Tyrannoraptora, Maniraptoromorpha, Maniraptoriformes, Ornithomimosauria, Ornithomimoidea, Ornithomimidae

Status: Extinct

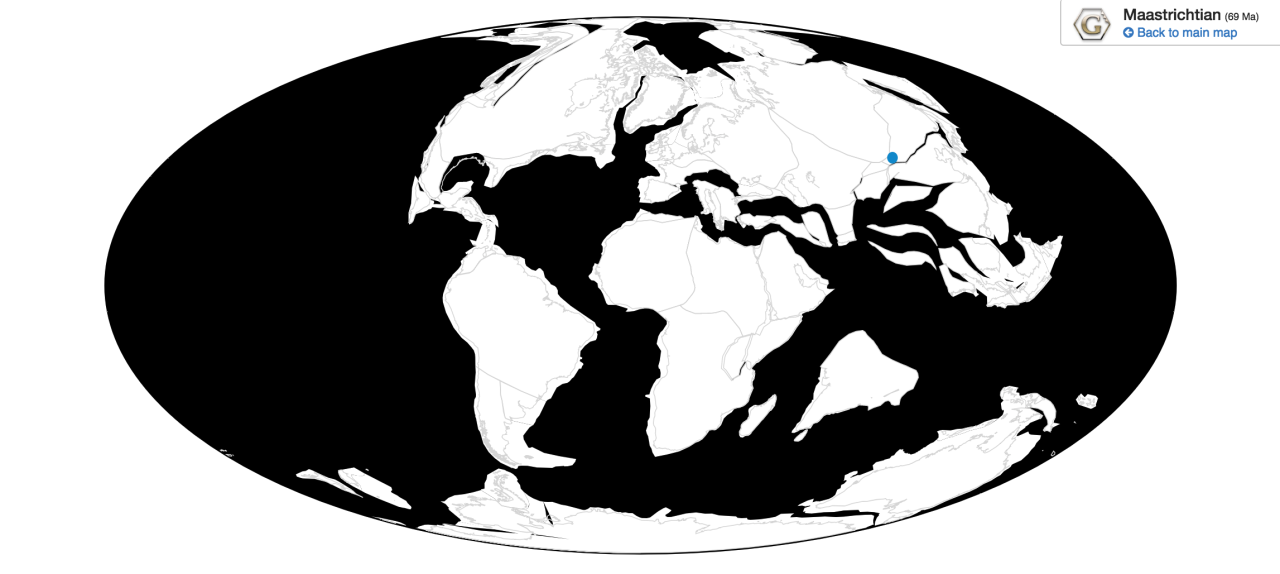

Time and Place: 70 million years ago; in the Maastrichtian of the Late Cretaceous

Found in the Nemegt Formation of Ömnögovi, Mongolia

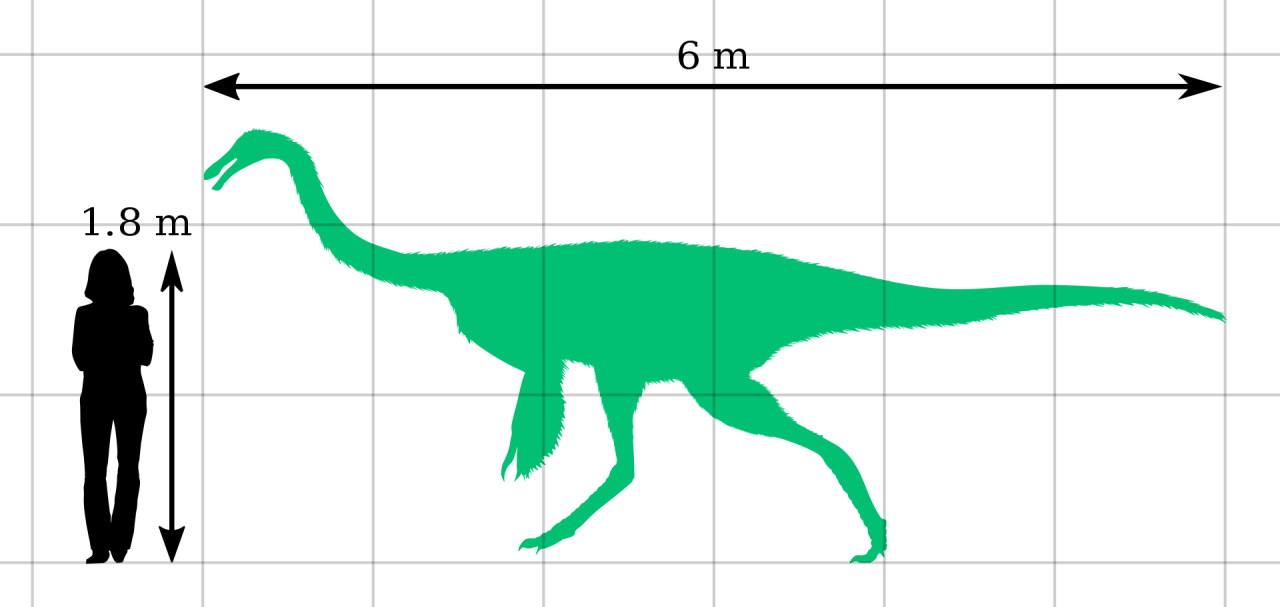

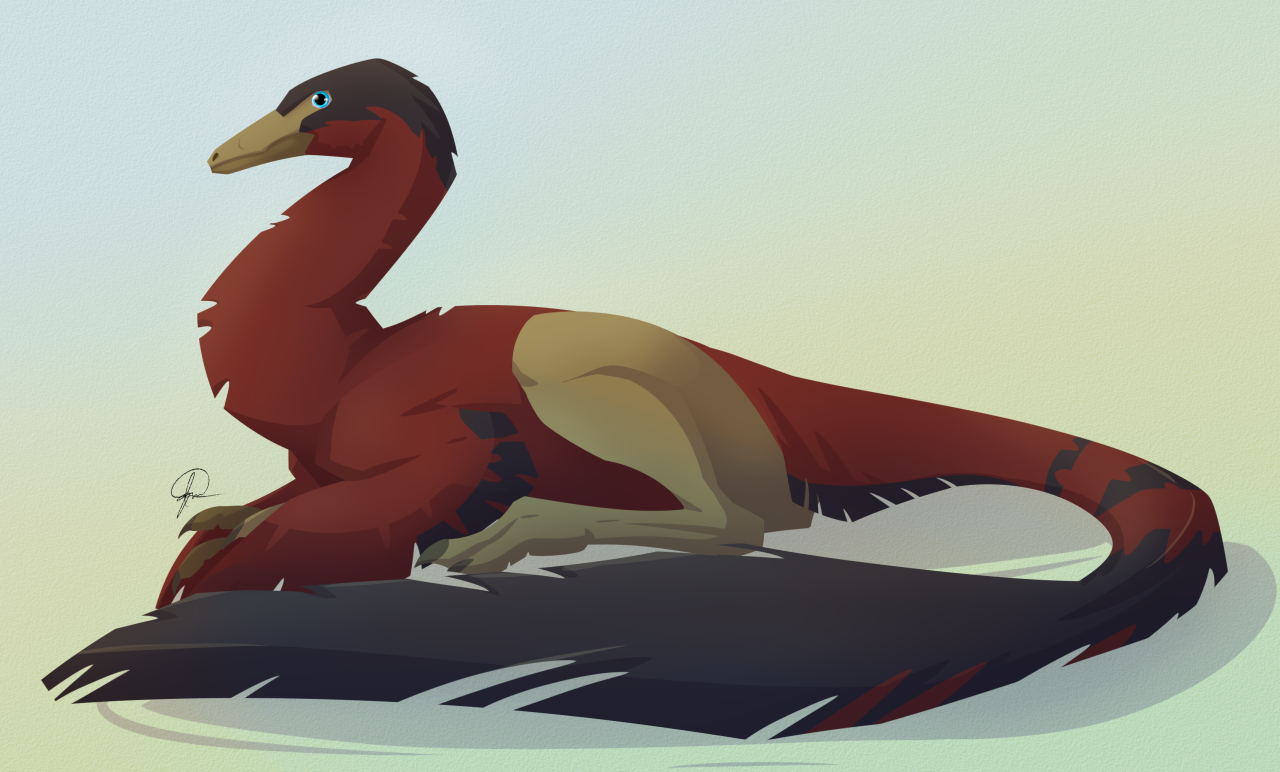

Physical Description: Gallimimus was a large, bipedal, fast dinosaur with the distinctive appearance shared by all Ornithomimid dinosaurs. It is, indeed, the largest species of Ornithomimid, ranging up to 6 meters in length and growing over two meters tall.

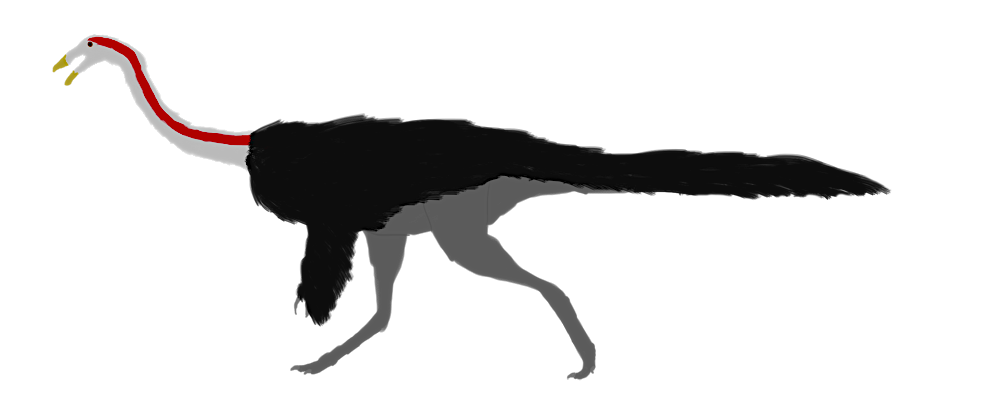

By PaleoGeekSquared, CC BY-SA 4.0

Being the largest Ornithomimid, it showcases most of the characteristics known from Ornithomimids, but larger. It had long legs built for fast and agile movements and a long tail for balance, like other members of the group. It had a long, slender neck and a small, narrow head. It also had long arms and, in general, a fairly elongated body. These animals, in short, resemble living dinosaurs such as Ostriches, but with more nonavian characteristics. Based on its closest relatives, it would have been at least somewhat decently feathered – with simple, single stranded protofeathers covering its body, tail, and neck; and longer feathers on the arms. These longer feathers were probably more complex and similar to living bird feathers (though not quite modern feathers), and would have been arranged to give the arms wing-like appearances. Still, their wings would not have been large enough to aid in locomotion, and instead were probably mainly used for display.

The head of Gallimimus was small, light, and narrow, supporting a toothless beak evolved independently from modern birds. Unlike other Ornithomimids, the beak did not narrow extensively towards the front into a point, but rather expanded out into something more akin to a bill. This actually is similar in its closest relative, Anserimimus, as well as the more distantly related Deinocheirus; which relates to the habitat they all share (see below). Younger Gallimimus actually had larger skulls compared to their bodies; so their heads shrunk as they age, along with the relative size of the eye compared to the rest of the head. A sheath of keratin – the same material that makes up hair and fingernails, as well as beaks – covered its mouth, and was probably smaller in terms of what part of the mouth it covered compared to North American Ornithomimids. It also had ridges on the inside of its mouth, like many species of modern duck. The eyes of Gallimimus were more to the side than in other theropod dinosaurs, which reflects its ecological position – as a prey animal, this would have allowed it to see more of its environment and see predators before they caught Gallimimus.

By Henry Thomas

Gallimimus also differed from its closest relatives in having a shorter spine, comparatively, which would have made it slightly squatter in appearance. It had very lightweight bones, filled with holes for air sacs, which would have made its breathing more efficient. The fact that it has the most lightweight bones of any Ornithomimid makes up for its particularly large size compared to its relatives. It had a longer neck compared to its body than other Ornithomimids as well, which it would have usually held upright rather than horizontally. It had high spines in its vertebrae which would have also arched the back slightly compared to its close relatives, giving it an even more distinctive appearance. Its arms, though long and covered in elongate feathers, would have been fairly weak and not used much for gathering food; the hands were also shorter than other Ornithomimids, which contributes to the idea that it didn’t use its hands in feeding. Instead, the wings would have mainly been display structures with other Gallimimus. Interestingly enough, the young might have used their hands more than the adults; the arms shortened in length during growth. The hips were fairly slender, like in other Ornithomimids; and it had long legs like other members of its group, indicating that it would have been as adept at running and maneuvering in its environment as other Ornithomimids.

Diet: Primarily herbivorous, feeding on water plants and other swam foliage much like modern ducks and turtles. Given its height and extensively long and flexible neck, it was probably a generalist browser, feeding on whatever plant material it could reach. It probably also occasionally fed on invertebrates in the water, though they would not have made up the bulk of its diet.

By Ripley Cook

Behavior: Gallimimus was an active, fast herbivore that probably had a warm-blooded metabolism like other dinosaurs (which is further corroborated by the fact that it was covered in feathers, like its close relatives.) However, despite its similarity in appearance to Ostriches, it probably wouldn’t have spent most of its time running across open plains and fields. Instead, given it lived mainly in a wetland and river environment, it would have utilized its speed to escape quickly. This would have made Gallimimus a fairly skittish animal, similar to other large, fast herbivores today. It probably lived in groups, as indicated by fossil trackways probably made by groups of Gallimimus on the floor of a pond; these groups would have foraged for plants together while some probably kept watch for predators. Since most dinosaurs exhibit parental care, it is likely that Gallimimus did as well; however, there is no direct evidence of such at this time, besides the fact that Gallimimus had wings with which to brood nests. Given that adult Gallimimus differed extensively in terms of arm proportions, they probably had distinct sexual display behaviors with their wings, and potentially courtship rituals, though this cannot be preserved to any extent in the fossil record.

Ecosystem: The Nemegt Formation was a wetland ecosystem filled with a wide variety of dinosaur types towards the end of the age of non-avian dinosaurs. Large river channels flooded the area, leading to extensive shallow lakes, mudflats, and floodplains similar to the modern Okavango Delta in Botswana. This swampy delta is reflected in the types of dinosaurs that frequent the region – in addition to the duck-like Gallimimus, other Ornithomimids included Deinocheirus (literally dubbed “Duck Satan”) and Anserimimus (the closest relative of Gallimimus, the name of which means Duck Mimic, so…), though Gallimimus was the most common by a large margin. These herbivores all specialized in feeding on water plants much like modern ducks, though probably not through filtering but rather browsing methods. Tall conifer trees and thick woods surrounded this wet environment, leading to an extremely rich environment that supported an extremely wide variety of dinosaurs and other animals.

By Tyler Young

Tarbosaurus, a large tyrannosaur very similar to Tyrannosaurus rex itself, has often been found directly associated with Gallimimus, indicating it probably preyed upon this dinosaur. This would have necessitated Gallimimus sticking together in large flocks to watch out for each other. In addition, Gallimimus is often found with Saurolophus, a large Hadrosaur, and they possibly even fed together on plant material in mixed groups. Other dinosaurs it is known to have lived directly alongside include the Troodontids Zanabazar and Borogovia, small intelligent predators that may have fed upon the young and eggs of Gallimimus.

Other dinosaurs that lived in the Nemegt, but not directly found with Gallimimus, include such Oviraptorosaurs as Avimimus, Elmisaurus, Conchoraptor, Nemegtomaia, Nomingia, and Rinchenia – these were medium sized, heavily feathered omnivores that probably fed on a variety of unexploited food sources in the area. The raptor Adasaurus also lived in the area and potentially posed a threat to younger Gallimimus. Other Troodontids were also present such as Tochisaurus. Opposite Birds were rarer, but present in the form of Gurilynia; the aquatic Hesperornithine Brodavis was also present, as was the modern bird Teviornis, which was a bird closely related to modern ducks and geese and thus also took advantage of the extremely wet habitat. Other herbivores included the hadrosaur Barsboldia, two Pachycephalosaurs (Homalocephale and Prenocephale), and two ankylosaurs (Tarchia and Saichania), which probably lived in drier areas of the ecosystem than Gallimimus. Nemegtosaurus, a titanosaur, also lived in the area. The Alvarezsaurid Mononykus lived in the area, and probably fed mainly on small invertebrates. Therizinosaurus also lived in the area, though it probably ate drier plant material than the other large, weird, herbivorous theropods of the area. Finally, Alioramus was another Tyrannosaur, though less bulky than Tarbosaurus, and as such it probably didn’t feed on Gallimimus as extensively.

By José Carlos Cortés

The ecosystem was, of course, not just made up of dinosaurs. At least one Azdarchid is known from the area, and it probably ate smaller individuals of Gallimimus. Buginbaatar, a type of mammal, lived in the environment and probably fed on smaller sources of food. Crocodylians would have also posed a threat to Gallimimus as they fed in the water environments. And, of course, a wide variety of turtles are known from the area, where they would have made up a notable part of the ecosystem.

Other:

Gallimimus is famous culturally for its portrayal in the film “Jurassic Park”, though it is not feathered in this film and is shown with its hands twisted in a way that dinosaurs could not do (having the palms facing the knees, aka pronated or “bunny hands,” would have broken the wrists; instead, dinosaurs such as Gallimimus have to face their palms towards each each other, as though clapping). In Jurassic Park, Gallimimus is shown flocking together in a large group, running away from Tyrannosaurus; though fossil evidence of this behavior isn’t know, it is not necessarily far from the truth, especially since the similar Tarbosaurus was in the environment and almost definitely preyed upon Gallimimus. At the time of its discovery and today, Gallimimus remains one of the best known Ornithomimid dinosaurs, helping us to understand this group as a whole.

~ By Meig Dickson

Sources

Barret, P. M. 2005. The diet of Ostrich dinosaurs (Theropoda: Ornithomimosauria). Palaeontology 48 (2): 347 – 358.

Gradzinski, R., J. Kazmierczak, J. Lefeld. 1968. Geographical and geological data form the Polish-Mongolian Palaeontological Expeditions. Palaeontologia Polonica 198: 33 – 82.

Holtz, T. R. 2014. Paleontology: Mystery of the Horrible Hands Solved. Nature 515 (7526): 203 – 205.

Hurum, J. 2001. Lower jaw of Gallimimus bullatus. In Tanke, D. H., K. Carpenter, M. W. Skrepnick. Mesozoic Vertebrate Life. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. 34 – 41.

Jerzykiewicz, T., D. A. Russell. 1991. Late Mesozoic stratigraphy and vertebrates of the Gobi Basin. Cretaceous Research 12 (4): 345 – 377.

Kielan-Jaworowska, Z., R. Barsbold. 1972. Narrative of the Polish-Mongolian Palaeontological Expeditions 1967-1971. Palaeontologia Polonica 27: 5 – 136.

Kobayashi, Y.; J.-C. Lü. 2003. A new Ornithomimid dinosaur with gregarious habits from the Late Cretaceous of China. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 48 (2): 235 – 259.

Kobayashi, Y., R. Barsbold. 2006. Ornithomimids from the Nemegt Formation of Mongolia. Journal of the Paleontological Society of Korea 22 (1): 195 – 207.

Lee, H. J., Y. N. Lee, T. L. Adams, P. J. Currie, Y. Kobayashi, L. L. Jacobs, E. B. Koppelhus. 2018. Theropod trackways associated with a Gallimimus foot skeleton from the Nemegt Formation, Mongolia. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 494: 160 – 167.

Madsen, E. K. 2007. Beak morphology in extant birds with implications on beak morphology in Ornithomimids. Dek Matematisk-Naturvitenskapelige Fakultet – Thesis. 1 – 21.

Makovicky, P. J., Y. Kobayashi, P. J. Currie. 2004. Ornithomimosauria. In Weishampel, D. B., P. Dodson, H. Osmólska. The Dinosauria (2nd ed.). Berkeley: University of California Press. 137 – 150.

Norell, M. A., P. J. Makovicky, P. J. Currie. 2001. The Beaks of Ostrich Dinosaurs. Nature 412 (6850): 873 – 874.

Novacek, M. 1996. Dinosaurs of the Flaming Cliffs. Bantam Doubleday Dell Publishing Group Inc. New York, New York.

Osmólska, H., E. Roniewicz, R. Barsbold. 1972. A new dinosaur, Gallimimus bullatus n. Gen., n. Sp. (Ornithomimidae) from the Upper Cretaceous of Mongolia. Palaeontologia Polonica 27: 103 – 143.

Osmólska, H. 1981. Coossified tarsometatarsi in theropod dinosaurs and their bearing on the problem of bird origins. Palaeontologica Polonica 42: 79 – 95.

Osmólska, H. 1982. Hulsanpes perlei n. G. n. Sp. (Deinonychosauria, Suarischia, Dinosauria) from the Upper Cretaceous Barun Goyot Formation of Mongolia. Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläontologie Monatshefte 7: 440 – 448.

Watabe, M., S. Suzuki, K. Tsogtbaatar, T. Tsubamoto, M. Saneyoshi. 2010. Report of the HMNS-MPC Joint Paleontological Expedition in 2006. Hayashibara Museum of Natural Sciences Reasearch Bulletin 3:11 – 18.

Watanabe, A., M. E. L. Gold, S. L. Brusatte, R. B. J. Benson, J. Choiniere, A. Davidson, M. A. Norell, L. Claessens. 2015. Vertebral pneumaticity in the ornithomimosaur Archaeornithomimus (Dinosauria: Theropoda) revealed by computed tomography imaging and reappraisal of axial pneumaticity in Ornithomimosauria. PLoS One 10 (12): e0145168.

Zelenitsky, D K., F. Therrien, G. M. Erickson, C. L. DeBuhr, Y. Kobayashi, D. A. Eberth, F. Hadfield. 2012. Feathered non-avian dinosaurs from North America provide insight into wing origins. Science 338 (6106): 510 – 514.