By José Carlos Cortés

Etymology: Recent Jaw from Asia

First Described By: Currie et al., 1994

Classification: Dinosauromorpha, Dinosauriformes, Dracohors, Dinosauria, Saurischia, Eusaurischia, Theropoda, Neotheropoda, Averostra, Tetanurae, Orionides, Avetheropoda, Coelurosauria, Tyrannoraptora, Maniraptoromorpha, Maniraptoriformes, Maniraptora, Pennaraptora, Oviraptorosauria, Caenagnathoidea, Caenagnathidae, Elmisaurinae

Status: Extinct

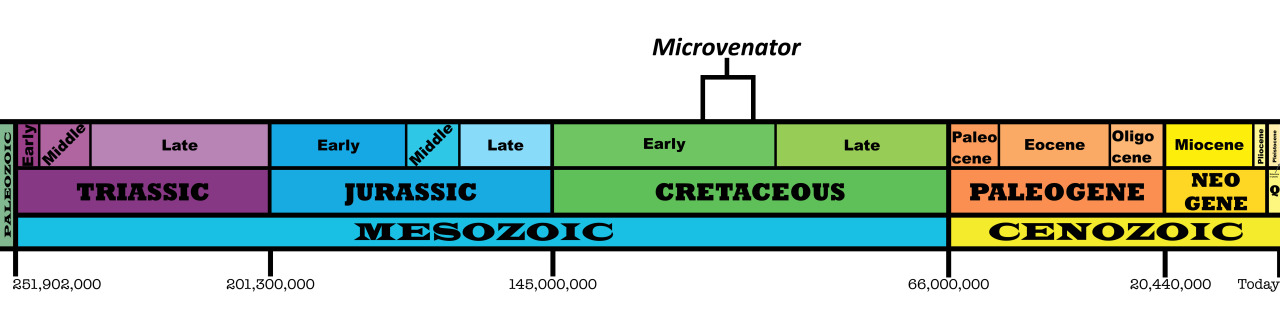

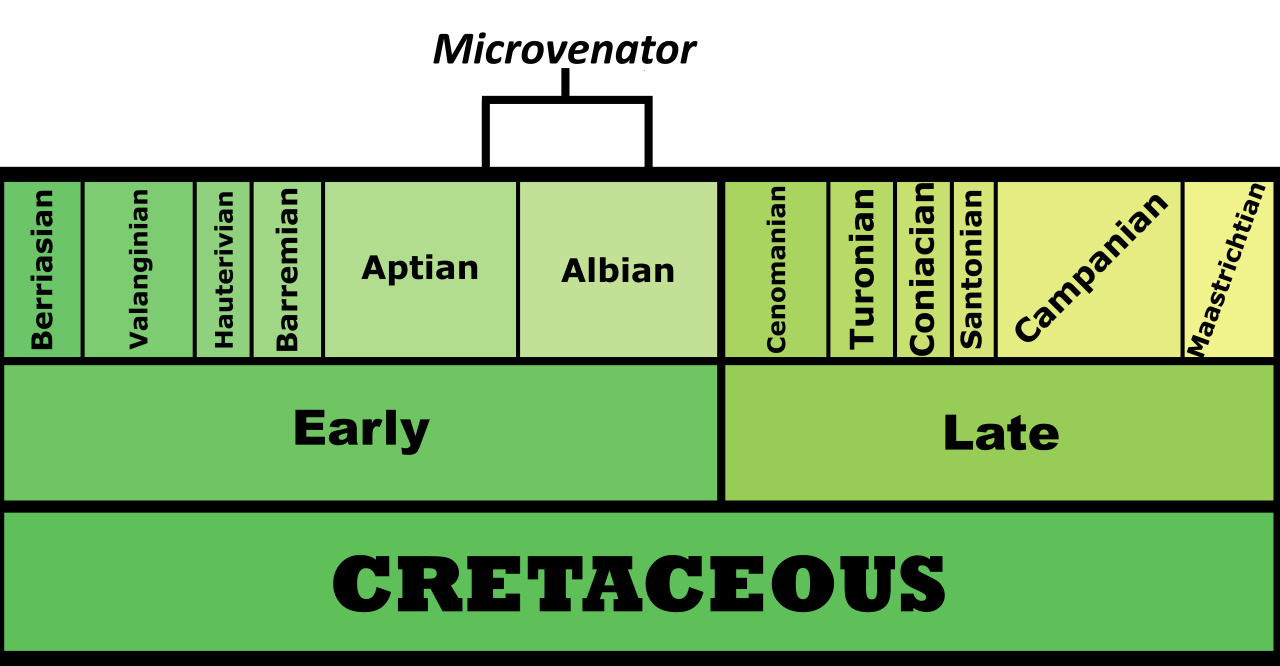

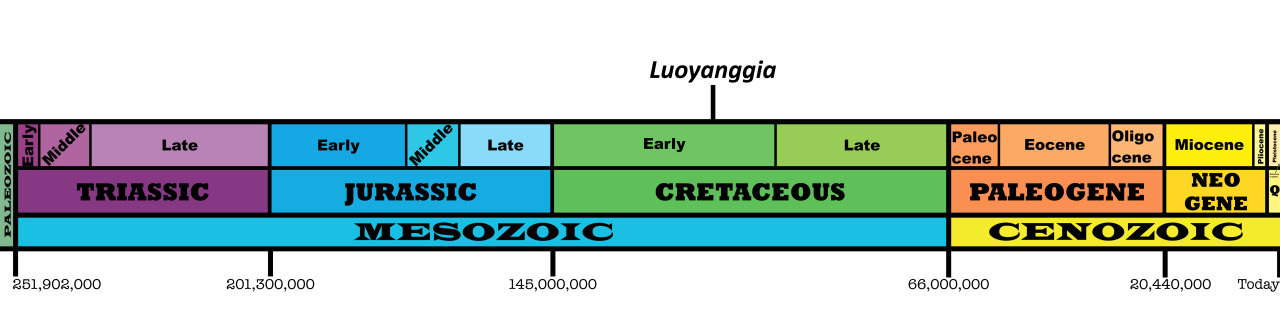

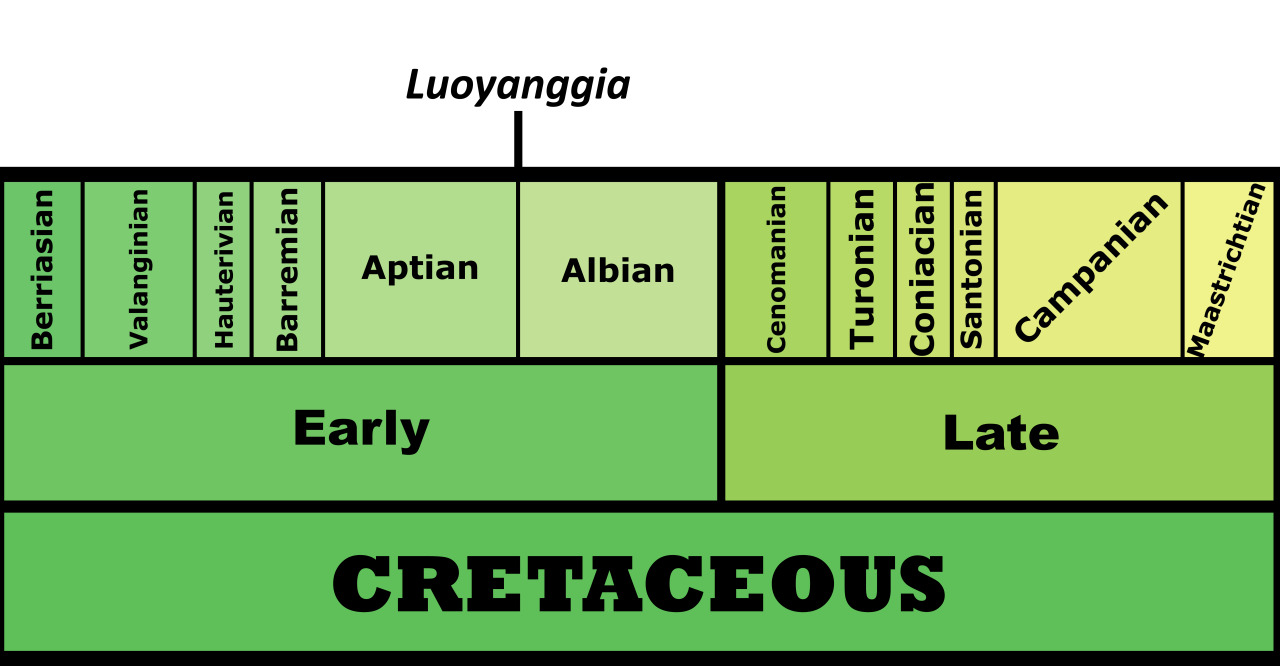

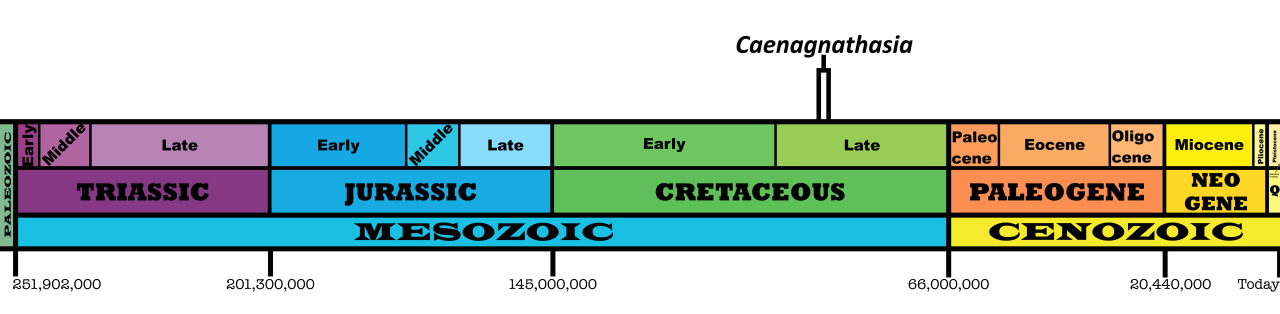

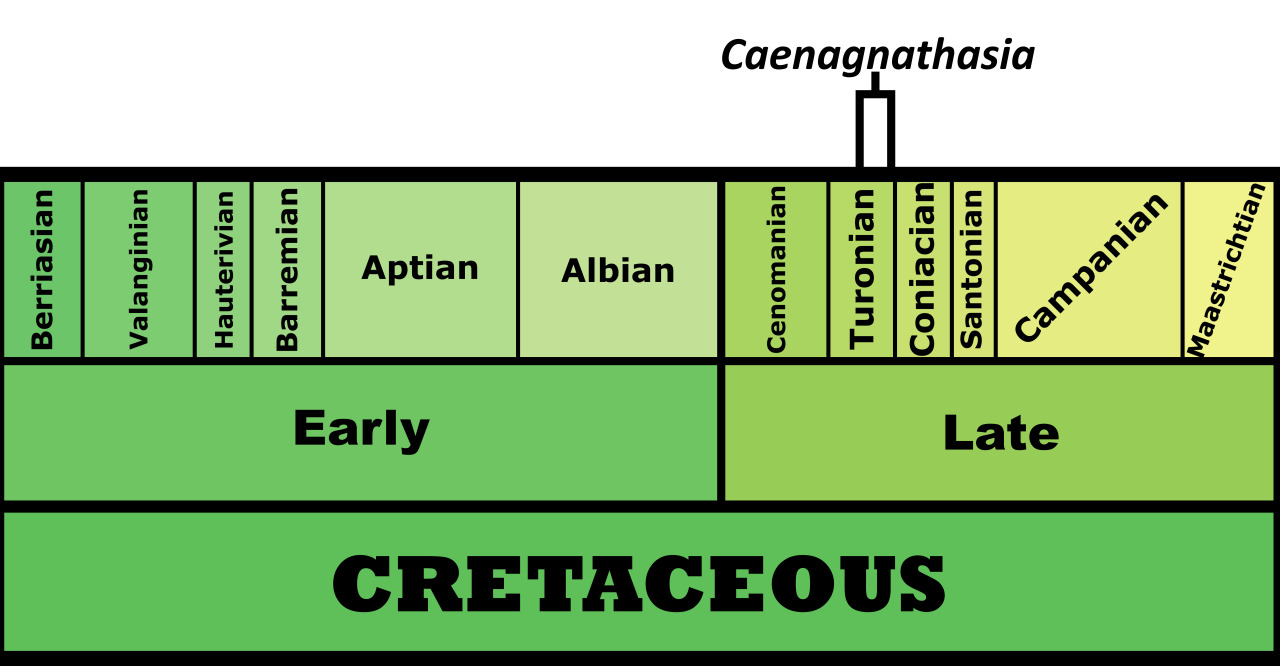

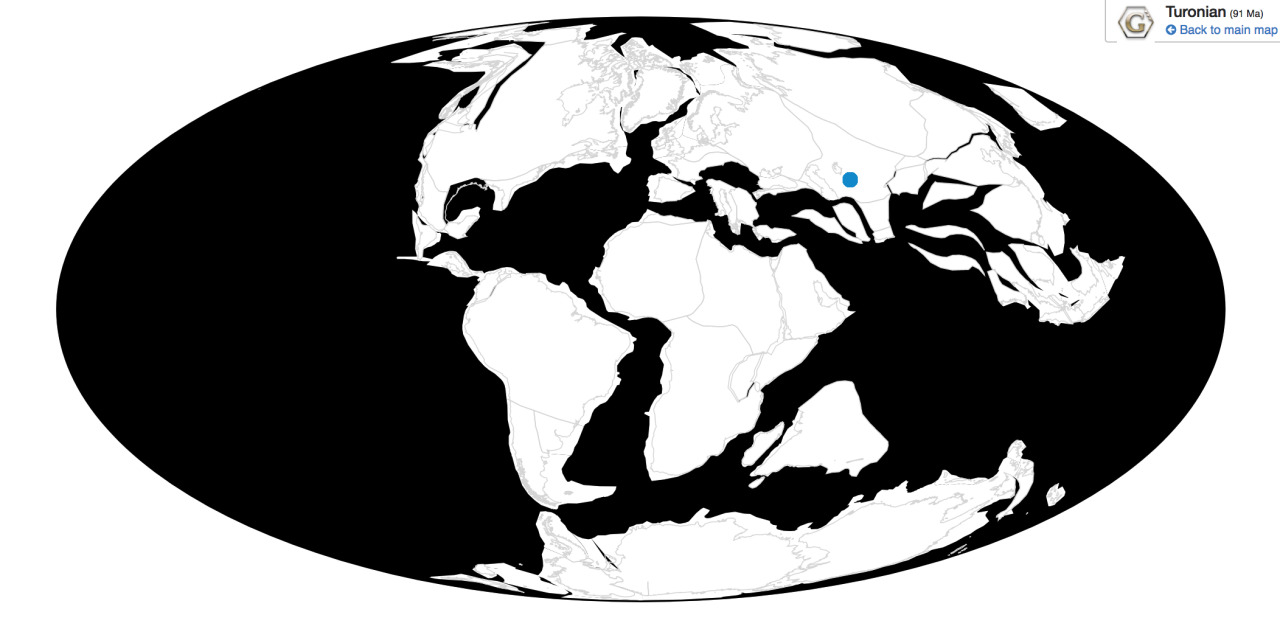

Time and Place: Between 92 and 90 million years ago, in the Turonian of the Late Cretaceous

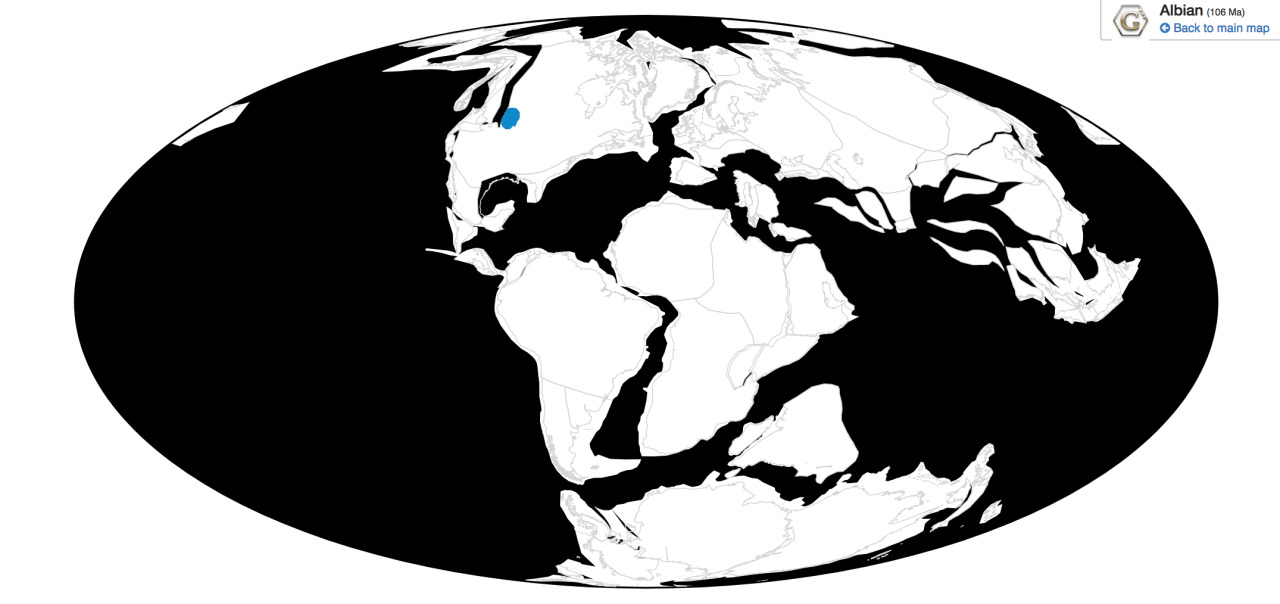

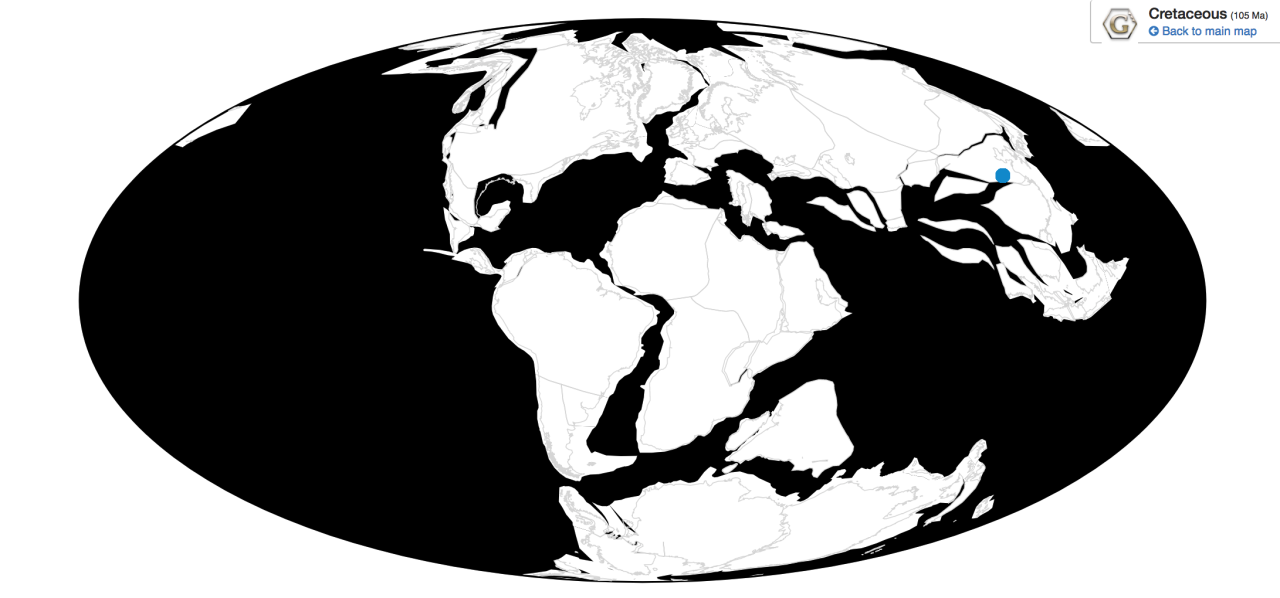

Caenagnathasia is known from the Bissekty Formation of Uzbekistan

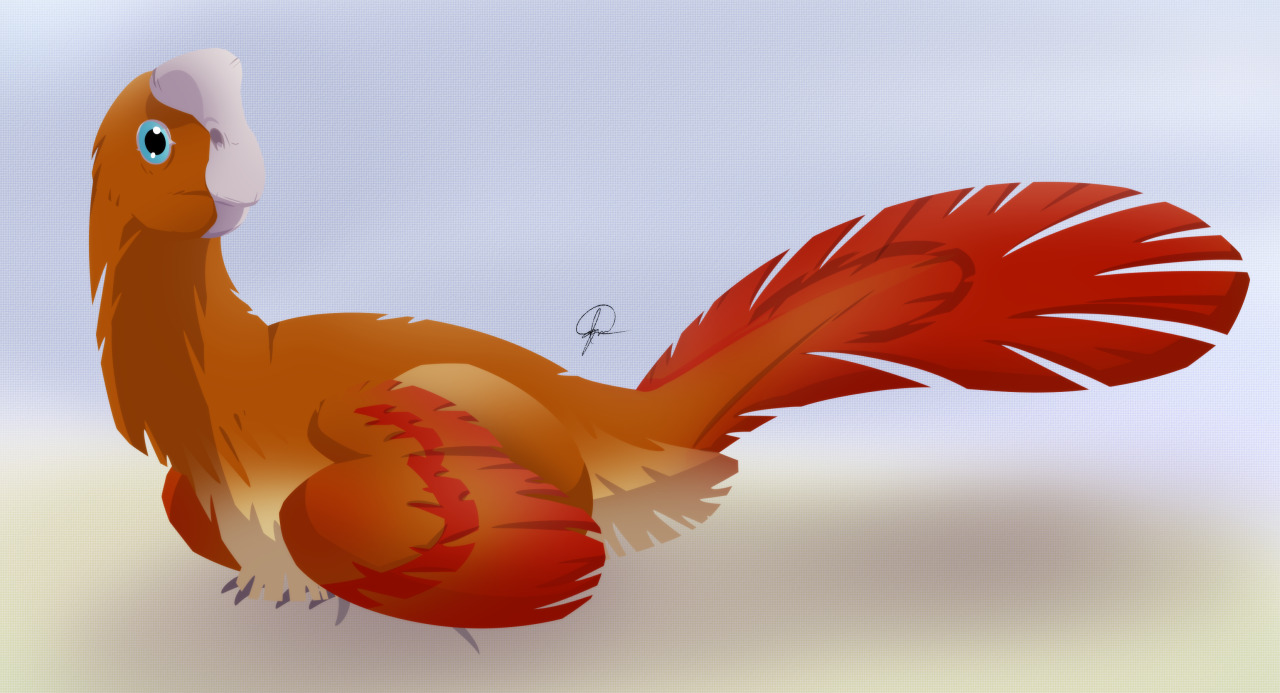

Physical Description: Caenagnathasia was a Chickenparrot, and of the kind with particularly long and shallow jaws, with complex ridges inside. Caenagnathids also were more lightly built than Oviraptorids, with more hollow bones, more slender arms and long, gracile legs. They also weren’t very adapted for running as in other Oviraptorosaurs. Caenagnathasia, however, is not very well known. It’s known from a few jaws from a few individuals, as well as some vertebrae and a femur. We do know that Caenagnathasia is one of the smallest known oviraptorosaurs, and one of the smallest non-avian dinosaurs on the whole. It probably was about 0.61 meters long, and weighed 1.4 kilograms. Other than that, it probably would have resembled other oviraptorosaurs in general – fully feathered and bird like, with extensive wings, a tail fan, a beak, and long legs. It also was probably one of the more basal Caenagnathids.

Diet: Like other Oviraptorosaurs, Caenagnathasia was probably an omnivore.

Behavior: It is likely that Caenagnathasia behaved similarly to other Oviraptorosaurs, though we have no proof either way on that score. It probably would have taken care of its young, creating a large nest with eggs laid around the edge. Caenagnathasia would then sit in the center of the nest and use its wings to keep the eggs warm, like modern birds. These eggs were ovular and elongated, and potentially teal or turquoise in color. Caenagnathasia would have also been an an active, warm-blooded animal, using its wings to communicate with other members of the species and in sexual display. It also would have probably been opportunistic in terms of food eaten, feeding on whatever it could get its wings on.

By Ripley Cook

Ecosystem: The Bissekty Formation was a diverse Middle Cretaceous seashore, filled with brackish swamps and braided rivers along the coast. It probably would have been filled with horsetails, cycads, ferns, and early flowering plants, though no plant fossils are known from the formation. There were a variety of animals in this ecosystem, especially many transitional forms to the iconic dinosaurs of the Late Cretaceous. There was Turanoceratops, a forerunner of Ceratopsids like Triceratops; Levnesovia, an almost-hadrosaurid, as well as other ornithopods Gilmoreosaurus and Cionodon; Bissektipelta, an ankylosaur; Timurlengia, a transitional Tyrannosaurid; Itemirus, one of the earliest known possible Velociraptorines; the troodontids Urbacodon and Euronychodon, and a variety of early birds such as Platanavis, Zhyraornis, and opposite birds like Abavornis, Catenoleimus, Explorornis, Incolornis, Kizylkumavis, Kuszholia, Lenesornis, and Sazavis. There was also a probable Ornithomimosaur that has not yet been named.

Non-dinosaurs were also present, including the huge pterosaur Azhdarcho, many different kinds of fish, some turtles, amphibians, and even sharks that were adapted to the ample brackish water. There were a lot of crocodylomorphs, too, like Zhyrasuchus, Zholsuchus, Kansajsuchus, and an alligatoroid, Tadzhikosuchus. There were also a lot of weird Iguanas, and early mammals as well – herbivorous Zhelestids, burrowing Asiorhyctitherians, insectivorous Zalambdalestids, almost-marsupials, and rodent-like Cimolodonts. This is surely an exciting ecosystem for further research, as it showcases a transition from the Early Cretaceous, to the Late.

Other:

~ By Meig Dickson

Sources under the Cut