By José Carlos Cortés

Etymology: Polar Bird

First Described By: Chatterjee, 2002

Classification: Dinosauromorpha, Dinosauriformes, Dracohors, Dinosauria, Theropoda, Neotheropoda, Averostra, Tetanurae, Orionides, Avetheropoda, Coelurosauria, Tyrannoraptora, Maniraptoriformes, Maniraptora, Pennaraptora, Paraves, Eumaniraptora, Averaptora, Avialae, Euavialae, Avebrevicauda, Pygostylia, Ornithothoraces, Euornithes, Ornithuromorpha, Ornithurae, Neornithes, Neognathae, Galloanserae, Anseriformes, Vegaviidae

Status: Extinct

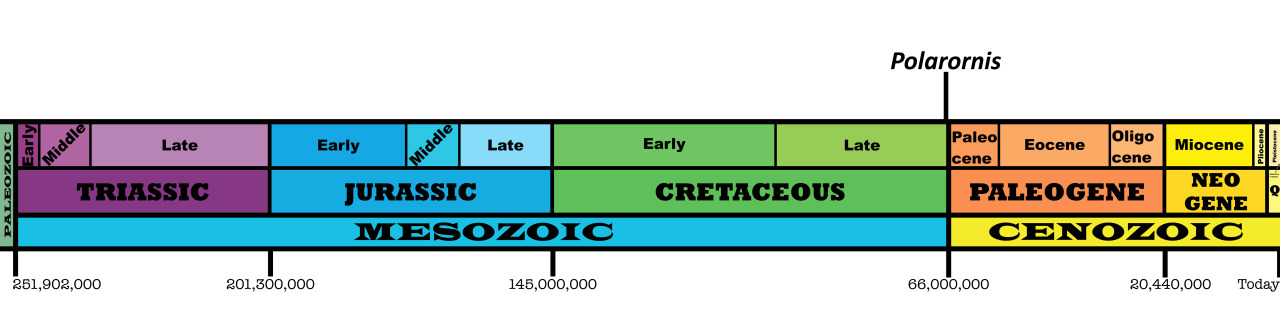

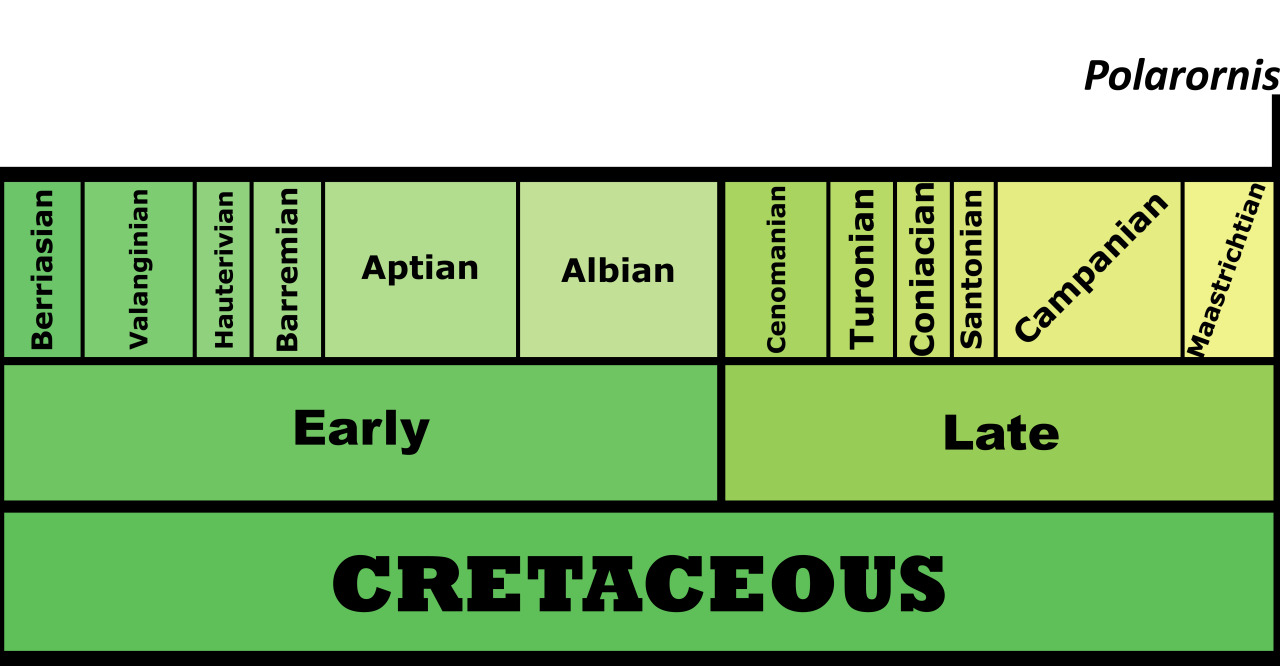

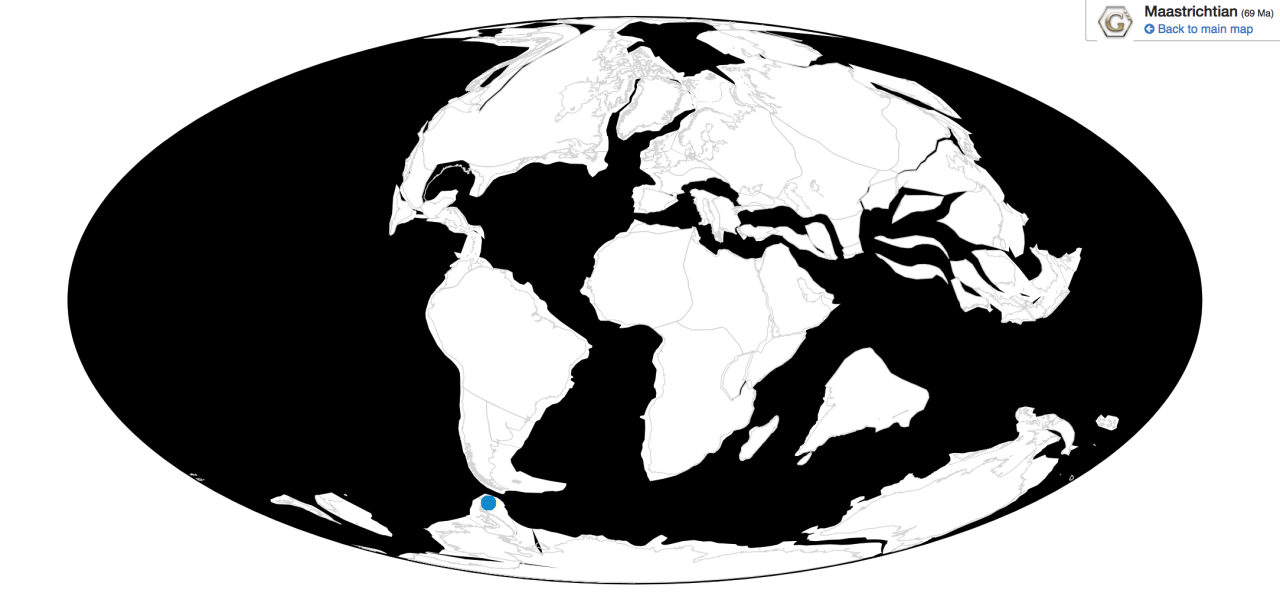

Time and Place: 66 million years ago, in the Maastrichtian age of the Late Cretaceous

Polarornis is known from the Lopez de Bertodano Formation of Seymour Island, Antarctica

Physical Description: Polarornis was a fairly long duck-like dinosaur, around 80 centimeters in body length, though its wingspan and tail length are unknown. It would have had a fairly long looking body, with a long head and long neck (there’s a reason it was mistaken as a loon); the length of its legs is fairly unknown, but it had a short thigh and also had strong calf muscles. It had a long, narrow, toothless beak as well. Its wings aren’t well known, and it had very dense bones, so it may have had small wing. This makes it a fascinating case of a duck that evolved to look weirdly loon-like – convergent evolution is amazing!

Diet: Polarornis probably fed mainly on fish and aquatic invertebrates, especially given how many were there in its environment!

Behavior: Polarornis seems to have been flightless or nearly so, and probably spent most of its time in the water and as a diving dinosaur. This makes it a bird very similar to modern penguins and to contemporary hesperornithines! It would have probably used its legs extensively to kick and paddle through the water in search of food. As a diving bird in the far south, it also probably would have spent a lot of time preening, to keep its feathers waterproof and able to keep in warm air to protect it from the environment.

As an Anseriform, it is likely that Polarornis would take care of its young, and live in family groups; Polarornis young grew very quickly, especially for dinosaurs at the time, which would help it in the highly seasonal climates of Antarctica at the time. but beyond that it’s difficult to say what it would have acted like, beyond “duck-like”.

By Scott Reid

Ecosystem: Polarornis lived in the Lopez de Bertodano Formation, an antarctic shorline ecosystem from right before the end-Cretaceous extinction. Though Polarornis is known from the layer right before the extinction, nothing else is known from the same layer except some invertebrates such as bivalves, gastropods, and cephalopods. This was a mild arctic coastline ecosystem, with maritime climate and the higher temperature of the planet making it warmer than it would be today, but still very chilly for Mesozoic standards. Here there were many mosses, hornworts, liverworts, ferns, clubmosses, conifers, proteas, and beech trees. Other dinosaurs known from the layer just below Polarornis – and thus may have been around with Polarornis, we can’t entirely rule it out – includes the ornithopod Morrosaurus, the Anseriform Conflicto, and another Vegaviid Vegavis – in fact, I wouldn’t be surprised if Polarornis was the descendant of Vegaviis! There was also the Elasmosaurid Aristonectes and the Mosasaurid Kaikaifilu, which may have fed upon Polarornis. The Lopez de Bertodano Formation is thus a beautiful snapshot of the evolution of avian dinosaurs right up to the extinction of their nonavian relatives.

Other: Polarornis was originally thought to be a loon, and only recent studies have indicated that it belongs with animals like Vegavis and Australornis, in an early family of duck-forms from across the Cretaceous-Paleogene boundary. Polarornis, amongst others, were some of the handful of dinosaurs able to survive the asteroid impact, giving us all the birds we have today!

~ By Meig Dickson

Sources under the Cut

Agnolín, F. L., F. B. Egli, S. Chatterjee, J. A. Garcia Marsà, and F. E. Novas. 2017. Vegaviidae, a new clade of southern diving birds that survived the K/T boundary. The Science of Nature 104(87):1-9

Chatterjee, S. 2002. The morphology and systematics of Polarornis, a Cretaceous Loon (Aves: Gaviidae) from Antarctica. Proceedings of the 5th Symposium of the Society of Avian Paleontology and Evolution 125-155

Clarke, J. A., C. P. Tambussi, J. I. Noriega, G. M. Erickson, and R. A. Ketcham. 2005. Definitive fossil evidence for the extant avian radiation in the Cretaceous. Nature 433(20):305-308

Rozadilla, S., F. L. Agnolin, F. E. Novas, A. M. Aranciaga Rolando, M. J. Motta, J. M. Lirio, and M. P. Isasi. 2016. A new ornithopod (Dinosauria, Ornithischia) from the Upper Cretaceous of Antarctica and its palaeobiogeographical implications. Cretaceous Research 57:311-324

Tambussi, C. P., F. J. Degrange, R. S. Mendoza, E. Sferco, and S. Santillana. 2019. A stem anseriform from the early Palaeocene of Antarctica provides new key evidence in the early evolution of waterfowl. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society